The Overtourism Debate at WTM 2025 – 5 Insights That Got Me Thinking

I went to World Travel Market London this year with a quiet challenge to myself. Basically, to open my mind and my ears and to listen 'freshly'. I notice in myself and in others that it's hard to see the walls of our silo and to recognise the reverberations of the echo chamber. So instead of listening to confirm what I already believe (apparently very common!), but to actively absorb information that might unsettle it.

That mindset led me into a session titled Rethinking Overtourism: Are We Ready for Real Accountability? Moderated by Aleix Rodríguez Brunsoms, Director of Strategy at Skift, the panel brought together Chris Fair (President & CEO, Resonance Consultancy), Joanna Reeve (General Manager UK & Ireland, Intrepid Travel), and Tolene van der Merwe (Director UK & Ireland, Malta Tourism Authority).

I’ve followed the overtourism conversation for years. It’s one of those topics that has propelled the conversation in sustainable and regenerative tourism circles. The debate challenged a number of my assumptions and also brought fresh perspectives that I hadn't previously considered. It really got me thinking about what overtourism actually is, who is responsible for it, and how we might respond.

Below are five reflections that stayed with me, not necessarily as conclusions, but as prompts for re-thinking.

1. We’ve let the overtourism narrative run away from us

Chris Fair opened with a provocation: the industry has allowed the overtourism narrative to dominate far too much. “It’s not an industry-wide problem,” he said. “It’s a localised one that appears in specific places at certain times.” That observation landed. In recent years, the overtourism story has been treated as a global indictment of tourism itself, rather than a set of context-specific challenges. The danger of that narrative is that it can obscure the majority of destinations where tourism is deeply positive - sustaining livelihoods, protecting heritage, and financing conservation. It also can diminish hope for destinations in very early stages of tourism development.

The takeaway for me was not to dismiss the term, but to use it precisely. There is a need for balance in the conversation, acknowledging where pressure points exist while also articulating where tourism genuinely adds value.

2. The root causes of overtourism often lie outside tourism

One of the most interesting threads of the discussion was how many of the forces shaping visitor pressure sit entirely outside the sector. Real-estate regulation, school calendars, transport networks, and social-media trends all play major roles in funnelling demand to the same few destinations at the same times of year. Tourism then becomes the visible face of wider societal dynamics, somewhat of a convenient scapegoat for systems we don’t collectively govern.

That reframing matters because it reminds destination leaders that effective management requires cross-sector collaboration: between planning departments, housing authorities, environmental agencies, and community representatives, not just tourism boards and operators. If the causes are systemic, so too must be the solutions.

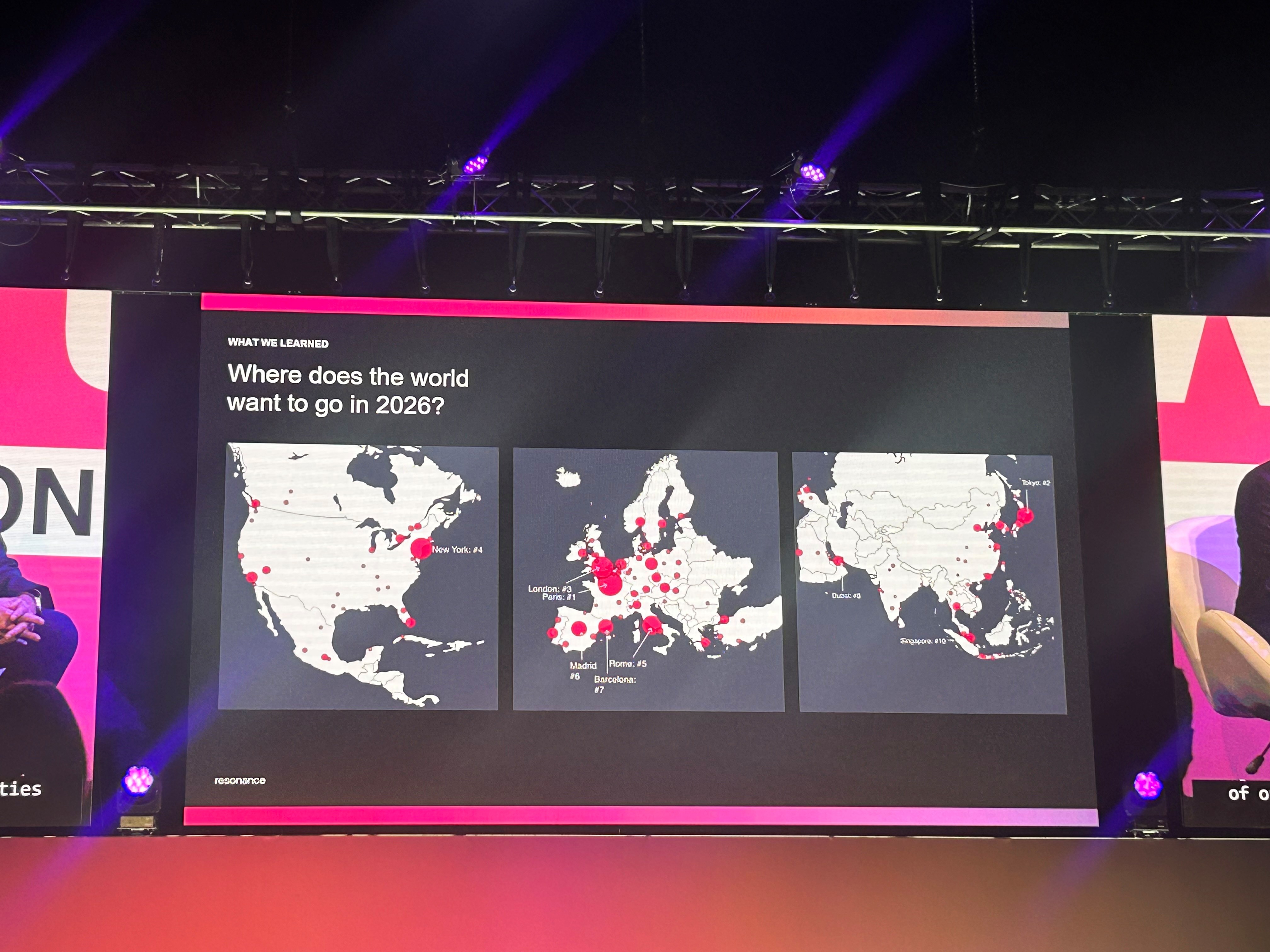

The data shared during the session reinforced this reality - see this screenshot. When asked where the world most wants to travel, the map was almost entirely lit up over Europe. Chris Fair shared some findings from the World Best Cities 2026 report. When asked what visitors plan to do, the hotspots were, once again, the hotspots. It’s a striking visual reminder that while the overtourism debate is loudest in Europe, it’s also where the majority of global travel demand still converges. Even as new destinations seek to attract visitors, the gravitational pull of the familiar - the icons, the “must-sees”, the bucket-list cities - continues to dominate.

Rather than dispersal, what we’re seeing is a concentration effect: a reinforcing loop of popularity, visibility, and access. That reality challenges the idea that overtourism can be solved by marketing alone. It calls instead for a more systemic conversation - one that recognises how education, mobility, and aspiration shape global travel flows just as much as tourism policy does.

3. Growth and prosperity are not the same thing

One question posed during the panel continues to echo for me: At what point does tourism growth stop being prosperity and start being dependency? It’s a brave question for any destination to ask, especially those where tourism supports a large share of GDP and employment. Yet it’s also a necessary one.

When success is measured only by arrivals, we risk designing systems that chase volume at the expense of resilience. Prosperity, in a place-based sense, is about diversity of value - economic, social, cultural, and ecological. Growth becomes sustainable only when it strengthens that diversity.

4. Accountability is shared, and that makes it complicated

All four speakers agreed that most governments already possess the tools to manage visitor flows, from zoning and taxation to housing policy and infrastructure planning. This means that the gap is relational rather than operational. Accountability, they suggested, fails when coordination and transparency falter. Tolene van der Merwe offered a refreshing perspective: “It’s not about bad tourists or bad operators. It’s about all of us working together with very different visions.”

That phrase ‘very different visions’ sums up the modern destination challenge. Alignment is ideal, but elusive and unlikely. The realistic opportunity may lie in constructive coexistence: building systems where competing visions can interact productively without collapsing into conflict.

5. The most promising responses come from collaboration, not control

Malta’s example illustrated this point well. While the country has introduced visitor caps and a transparent tourism tax, the intent is restorative rather than restrictive. Revenue is reinvested into local infrastructure, smart-bin technology, and beautification projects that benefit residents first and visitors second. This approach reframes regulation as stewardship. It’s about managing tourism as a shared resource rather than a commodity to be maximised or a problem to de contained. That may serve as a maturity test for any destination: whether its policies are built on control or on collaboration.

Where this leaves us

Listening to that discussion, I realised that overtourism is as much a governance problem and a perception problem as a capacity problem. It revealed how deeply the industry is still shaped by outdated assumptions about growth, success, and public value. What might change if we treated overtourism not as a crisis of numbers, but as a mirror reflecting the health of the wider system? If we looked beyond the headline and asked, what does this say about how we plan, measure, and communicate tourism’s role in society?

Those are uncomfortable questions and they are also generative ones. After all, questioning what we think we know has always been the path to progress.